Born in 1852 in Adelaide, Emilie Appelt (née Temme) wrote a detailed, personal, diary between 1904 and 1914. By 1904, the then fifty-two-year-old had already lived an extraordinary life – she witnessed the rapid growth of Eudunda, lived through drought and famine, and had borne thirteen children, six of whom she buried.

She witnessed the rise of Eudunda, including the advent of the railway in 1878. She was present at the opening of St John’s Lutheran Primary School, Eudunda, and Concordia College, Adelaide, both of which occurred in early 1905. She recorded terrible accidents that occurred locally – drownings, crashes, near misses with horses – and more.

Her home on South Terrace, Eudunda was a revolving door of students, pastors, clergymen and friends new and old from across the country. Through her diaries we learn of the interconnectedness between the Lutheran Church in Eudunda and theological institutions in America and Germany. Her diary betrays a mother’s love for her children, as she writes of them and their endeavours constantly. Emilie was a German in a pre-war time, when a Germanic background was something to be proud of.

Writing across ten tumultuous years at the turn of the twentieth century, Emilie witnessed the changing fortunes of a rural commercial hub until the eve of World War One, a seismic event that would transform her life, and may have caused the abrupt end to her diary due to military intervention. Her diary records a community on the precipice of change and is punctuated by personal, political, cultural, social, and religious facets, illuminating our understanding of that time.

Emilie’s husband prominently features in the general historical record – he was a local magistrate, Justice of the Peace, choirmaster, and business owner, among other positions – yet Emilie does not feature. Her diary brings to light her voice, her perspective, her experience. It was a private place for her to vocalise her beliefs, fears, wishes, joys and concerns in a male-dominated age.

Emilie’s personal musings are a rarity: surviving diaries written by Lutherans from this time are almost unheard of, diaries written by women are rarer still. Her diary sheds light on a pre-war era now lost to us, and it is important to understand the value of records of this calibre, learn from the stories they impart and understand how they speak to us today.

——

That Emilie’s diary exists is remarkable. The diary abruptly ended on 31 December 1914 with a brief note that she had attended communion on the last night of the year. Anti-German xenophobia, caused by World War One, may have caused the diary’s end, as in early 1915, the German-born pastor of Emilie’s congregation, and her dear friend, was arrested and taken to Adelaide. Weeks later, military forces surrounded the town, targeting German homes and businesses to find suspicious material.

The translator of the diary, Vida Hoopmann (née Appelt), who was one of Emilie’s daughters, may have stopped the diary. She may have felt the war years, as well as her mother’s declining health, were too emotionally damaging. Alternatively, she may have ceased translation, with every intention to resume translating.

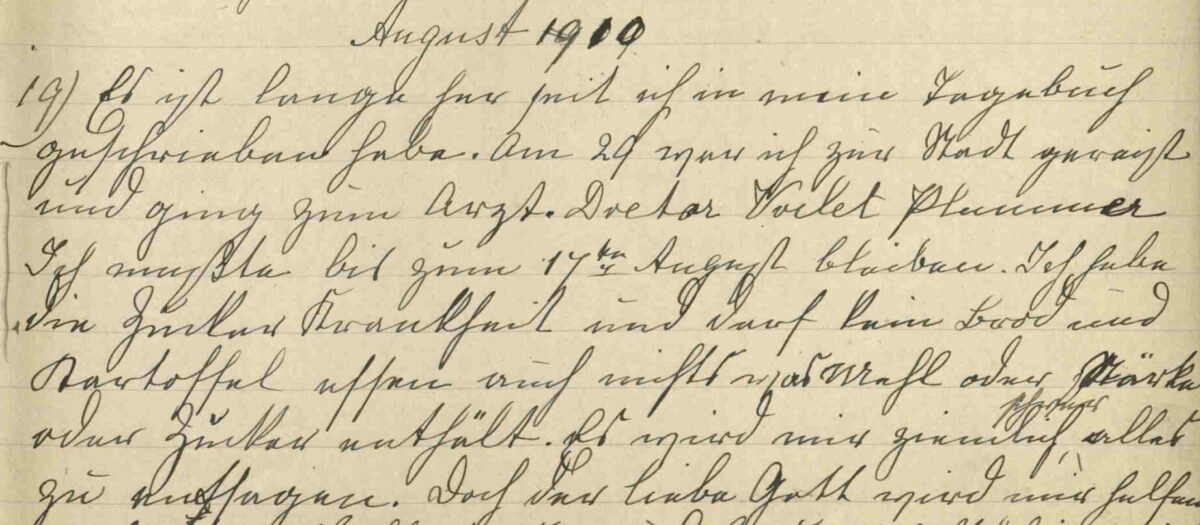

At present, only one volume of the original diary is known to exist. It is held by the Lutheran Archives and spans from April 1908 to August 1912. It is written in a spidery, but elegant, German hand. Vida translated the diary possibly between 1938, when Emilie’s husband died, and 1978, when Vida herself died. Family anecdotes do not shed any light on this. Without Vida’s translation, much of the diary would have been lost.

When it came to publishing the diary, the first step was to digitise it. It had only existed in a hardcopy typed format following translation. Optical Character Recognition (OCR) technology was utilised to speed the process, though precise editing was still required.

——

The author, Samuel Doering, recently graduated with First Class Honours in History and English from the New College of the Humanities, London. He also appears on ABC Radio with Peter Goers, and writes for Art UK.

He stumbled across the transcript of the diary in 2018 in the cold and crowded archive room at the Eudunda Family Heritage Gallery. Despite the discomfort, he read the diary in its entirety, marvelling at the episodes she recorded. Excerpts had been disseminated locally, but the full extent of her diary remained largely obscured. Aware of the diary’s exceptional singularity, Samuel faithfully edited Emilie’s decade-long diary, shedding light on the scenes she witnessed through stunning new research. The Diary of Emilie Appelt: Eudundan. German. Lutheran. Woman. 1904-1914. is his first book.